http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/3374.html

1. Disruptive innovations spur growth.

Companies have two basic options when they seek to build new-growth businesses. They can try to take an existing market from an entrenched competitor with sustaining innovations. Or they can try to take on a competitor with disruptive innovations that either create new markets or take root among an incumbent's worst customers. Our research overwhelmingly suggests that companies should seek out growth based on disruption.

Sustaining innovations, whether they involve incremental refinements or radical breakthroughs, improve the performance of established products and services along the dimensions that mainstream customers in major markets historically have valued. Examples: a microprocessor that enables personal computers to operate faster and a battery that lets laptop computers operate longer.

All Innovative ideas start out as half-baked propositions.

— Clayton M. Christensen, Michael E. Raynor,

and Scott D. Anthony

Companies march along a performance trajectory by introducing successive sustaining innovations—first to remain competitive in the short term. But, as noted in The Innovator's Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail (Harvard Business School Press, 1997), firms innovate faster than our lives change to adopt those innovations, creating opportunities for disruptive innovations. Although sustaining innovations move firms along the traditional performance trajectory, disruptive ones establish an entirely new performance trajectory.

Disruptive innovations often initially result in worse performance compared with established products and services in mainstream markets. But disruptive innovations have other benefits. They are often cheaper, simpler, smaller, and more convenient to use.

Consider the small off-road motorcycles introduced by Honda in the 1960s, Apple's first personal computer, and Intuit's QuickBooks accounting software. These innovations all initially underperformed the mainstream offerings. But they brought a different value proposition to a new market context that did not need all of the raw performance offered by the incumbent. They all created massive growth; to flip Joseph Schumpeter's famous phrase, creative destruction, on its head, this is creative creation. After taking root in a simple, undemanding application, disruptive innovations inexorably get better until they change the game, relegating previously dominant firms to the sidelines in often stunning fashion.

Incumbents almost always win battles of sustaining innovations. Their superior resources and well-honed processes are almost insurmountable strengths. Incumbents, however, almost always lose battles where the attacker has a legitimate disruptive innovation. To create a new-growth business, companies—established incumbents and start-ups alike—must be on the right side of the disruptive process by launching their own disruptive attacks.

2. Disruptive businesses either create new markets or take the low end of an established market.

There are two distinct types of disruptive innovations. The first type creates a new market by targeting nonconsumers, the second competes in the low end of an established market.

In a new-market disruption, attackers take root in a new "plane" of competition or a new context of use outside of an existing market. Consumers historically locked out of a market because they lacked the skills or wealth welcome a relatively simple product that allows them to get done what they had always wanted to get done. These markets typically start out small and ill defined. They don't meet the growth needs of large companies. And the incumbent feels no pain at first. Because it creates new consumption, the disruptor's growth doesn't affect the incumbent's core business. But as the innovation improves, it begins to pull customers away from the incumbent. And the incumbent doesn't have the ability to play in this new game.

Managers must be patient for growth but impatient for profitability.

— Clayton M. Christensen, Michael E. Raynor,

Scott D. Anthony

Transistors were a disruptive innovation. Mainstream suppliers of tabletop radios, which were made with vacuum tubes, couldn't figure out how to use transistors because they couldn't initially handle the power requirements of these components. Then in 1955, Sony introduced the pocket radio. It was a static-laced product with horrible fidelity. But it enabled teenagers to do something that they couldn't before—listen to rock'n'roll out of their parents' earshot. Had Sony targeted consumers in established markets, the pocket radio would have bombed. But for teenagers, the alternative to a Sony pocket radio was no radio at all. By competing against nonconsumption, Sony set a very low technical hurdle for itself: The product just had to be better than nothing in order to find delighted consumers.

The second type of disruptive innovation takes root among an incumbent's worst customers. These low-end disruptions do not create new markets, but they can create new growth. The disruption of integrated steel mills by steel minimills demonstrates how low-end disruptors harness what we call asymmetries of motivation.

Minimills first took hold in the steel industry in the mid-1960s. They were very efficient. They had a 20 percent cost advantage over integrated mills. But the quality of the steel they produced was inferior. The rebar market at the bottom rung of the industry (rebar is small steel bars made from scrap and used to create reinforced concrete) was the only market that would accept the minimills' steel.

As the minimills entered the rebar market, the integrated mills were happy to exit it. Their gross margins in the rebar business were a mere 7 percent, and rebar accounted for only 4 percent of the industry's tonnage. So the integrated mills decided to focus on higher-profit steel products. The minimills made boatloads of money until they finally drove the last of the integrated mills out of the market—and then the price of rebar dropped 20 percent, because rebar had essentially become a commodity market. The minimills' reward for victory was that none of them could make money.

To make attractive money again, the minimills had to figure out how to make better-quality steel in larger shapes—not only angle iron but also thicker bars and rods. Profit margins in this market tier were 12 percent, almost double those of the rebar market; the overall market was also twice as large. So the minimills invested in equipment to make the larger pieces and worked to improve the quality and consistency of their steel. As the minimills began making inroads with better and bigger steel, the integrated mills were happy to exit this market tier to concentrate on more profitable products. When the last integrated mill left the market, the price of angle iron collapsed. Once again, the minimills had to move up to the next tier of the industry in order to survive. And so on.

At each stage of the minimills' climb up-market, an asymmetry of motivation was at work. For the minimills, the need to enter a more profitable market provided the motivation to solve the technological hurdles preventing them from producing higher-quality steel. The integrated mills were happy to leave these markets because the lower tiers in their product mix were always less profitable than products targeting higher-end customers. Eventually, of course, the integrated mills ran out of markets to flee to.

3. Disruptive opportunities require a separate business-planning process.

All innovative ideas start out as half-baked propositions. They then go through a shaping process as they wind their way through the organization to reach senior management. When firms have a single process for all the various forms of innovation, what comes out the other end of the process looks like what has been approved in the past, and it all looks like sustaining innovations.

Consider IBM's efforts to introduce voice-recognition software. Early iterations of IBM's ViaVoice software package featured IBM's "ideal" customer on the front: an administrative assistant sitting in front of her computer, speaking into a headset. It is easy to see why IBM targeted such customers. They constituted a large, obvious market, well aligned with IBM's needs and capabilities. But think about IBM's value proposition to this woman. She types 80 words a minute and almost never makes a mistake. IBM was telling her, "Why don't you change your behavior and use a system that gives you lower accuracy and slower speeds. We promise future releases will get better." The only way to attract great typists would be for voice recognition to be faster and more accurate than typing. This is a very high technical hurdle.

Where has voice-recognition technology begun to take off? Kids love the ability to tell their animated toys to "stop" or "go." "Press or say one" menu commands are another obvious application. In these contexts, people are delighted with a crummy voice-recognition product. Another good market for the technology may be all those executives you see standing in airport lines, trying to punch messages into their BlackBerries. Their fingers are too big to enable accurate typing—they'd be more than happy with a voice-recognition algorithm that's only 80% accurate.

Not surprisingly, disruptive ideas stand a small chance of ever seeing the light of day when they are evaluated with the screens and lenses a company uses to identify and shape sustaining innovations. Companies frustrated by an inability to create new growth shouldn't conclude that they aren't generating enough good ideas. The problem doesn't lie in their creativity; it lies in their processes.

Only by creating a parallel process for developing and shaping disruptive ideas—one that acknowledges their distinctive features—can companies successfully launch disruption after disruption. Such a process relies more on pattern recognition than on data-driven market analysis. After all, markets that do not exist cannot be analyzed. Even when numbers are available, they are never clear.

An intuitive process can still be rigorous if managers use the right tools. For example, discovery-driven planning lets you create a plan to test assumptions; aggregate project planning helps you allocate resources between sustaining and disruptive opportunities; the "schools of experience" theory informs hiring decisions.

4. Don't try to change your customers—help them.

Faulty market segmentation schemes help to explain the stunningly high rate of failure of new-product development. Most companies define markets in terms of product categories and demographics. We just don't live our lives in product categories or in demographics. When companies segment markets this way they often fail to connect with their customers.

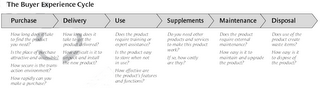

How do we live our lives? During the course of the day, problems arise, jobs we need to get done. We look around to hire products to get those jobs done. Products that successfully match the circumstances we find ourselves in end up being the real "killer applications." They make it easier for consumers to do something they were already trying to accomplish.

Some manufacturers pushed digital cameras based on the value proposition that they made it easy to edit out the red eyes from all your images and create an online album of your best photos. Research shows, however, that 98 percent of all photos get looked at only once. Only the most conscientious of us prioritized editing images or creating albums. Where digital camera makers found success was in marketing their products to consumers who used to order double prints of their photos and mail them to relatives. The digital technology enables consumers to use the Internet to do more easily what they already wanted to do.

A business plan predicated upon asking customers to adopt new priorities and behave differently from how they have in the past is an uphill death march through knee-deep mud. Instead of designing products and services that dictate consumers' behavior, let the tasks people are trying to get done inform your design.

5. Integrate across whatever is not good enough.

One critical decision firms face when creating an innovation-driven growth business is determining its optimal scope. Specifically, which activities need to be managed internally and which can be safely outsourced?

The answer often is driven by the fad of the day. During the 1960s, everyone thought IBM's integration was an unassailable point of competitive advantage. Because IBM controlled such a wide swath of the industry's value chain, it could make better products than anybody else. So companies copied IBM and tried to integrate. In the 1990s, everyone thought that Cisco's disintegrated business model that made extensive use of outsourcing was an unassailable point of competitive advantage. So companies jumped on this new bandwagon and sought to disintegrate.

The critical question is: What are the circumstances in which my firm should be integrated and what are the circumstances in which my firm can be a specialist? Integration provides advantages whenever a product is not good enough to meet customer needs. Proprietary, interdependent architectures allow companies to run multiple experiments, pushing the frontier of what is possible. Engineers can reconfigure their systems to wring the best performance possible out of the available technology.

Think about the computer industry. In its early days, you simply couldn't exist as a specialist provider. There were too many unpredictable interdependencies across every interface in the first mainframes. The manufacturing process depended on the design of the computer and vice versa. The design of the operating system affected the design of the logic circuitry. IBM had to be integrated across the entire value chain to produce a mainframe that came close to meeting its customers' needs.

By contrast, the modular architectures that characterize disintegration always sacrifice raw performance. Stitching together a system with partner companies reduces the degrees of design freedom engineers have to optimize the entire system. But modular architectures have other benefits. Companies can customize their products by upgrading individual subsystems without having to redesign an entire product. They can mix and match components from best-of-breed suppliers to respond conveniently to individual customers' needs.

But even in a modular architecture, successful companies still are integrated—just in a different place. Consider the computer industry in the 1990s. The computer's basic performance was more than good enough. What did customers want instead? They wanted lower prices and a computer customized for their needs. Because the product's functionality was more than good enough, companies like Dell could outsource the subsystems from which its machines were assembled. What was not good enough? The interface with the customer. By directly interacting with customers, Dell could ensure it delivered what customers wanted—convenience and customization. Value flowed to Dell and to the manufacturers of important subsystems that themselves were not good enough, like Microsoft and Intel.

In short, companies must be integrated across whatever interface drives performance along the dimension that customers value. In an industry's early days, integration typically needs to occur across interfaces that drive raw performance—for example, design and assembly. Once a product's basic performance is more than good enough, competition forces firms to compete on convenience or customization. In these situations, specialist firms emerge and the necessary locus of integration typically shifts to the interface with the customer.

6. Be patient for growth but impatient for profitability.

Managers inside new-growth businesses often feel tremendous pressure to quickly ramp up sales volume. But disruptive businesses can't get big very fast. The only way to make them grow quickly is to cram them into large, obvious markets. In established markets, customers don't care about the disruptive innovation's strengths. They only care about its weaknesses. This is a recipe for disaster, and one reason why company-backed disruptive ventures can have a leg up. Venture capitalists have become increasingly impatient for businesses to get huge. As long as their core businesses are growing healthily, companies will find it easier to wait for the disruptive businesses to find a foothold market and slowly build commercial mass.

Managers must be patient for growth but impatient for profitability. When you are willing to put up with a lot of losses before a disruptive business turns profitable, that means you are trying to lay the foundation for a huge new business. Insisting on early profitability pushes the new disruptive business to find the markets where its unique capabilities will be uniquely valued. Forced to keep its fixed costs low, the new business can serve small customers who would not meet the needs of a high fixed cost structure.

Managers in large companies who read

The Innovator's Dilemma may have finished the book thinking they're destined to fail, no matter what they do. We hope to shift their sentiment from despair to hope. If managers understand the theories of innovation, they have the ability to create new-growth businesses again and again.